Collaborative Platforms for Synthetic Biology

Introduction

In this post I give rundown of some key points I distilled from OECD study “Collaborative platforms for emerging technology: Creating convergence spaces” that appeared last year in the series OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers. The study aims to support policy makers and innovators to realize the potential of emerging technologies through collaborative platforms. What is a collaborative platform I hear you ask? Don’t worry we will get there.

The question I focused in this overview mainly on is: “What policies would allow the expansion of biological engineering and enable broader community of innovators to commercialize new bio-based products?”

Why is this important? Private actors always face risks with new investments, and engineering biology is no exception. Usual financial risks are exacerbated by longer development times and customer opinion on biologically engineered products can shift rapidly to unfavorable stance. Consequently, strong public support is usually needed to make the investments attractive.

Collaborative platforms

OK, back to your question - what are those collaborative platforms? In a nutshell collaborative platforms:

- are organizational arrangements around shared resources, across private and public sector

- allow different partners (across academia, industry and public sphere) to work together in new ways, accelerating innovation and value creation

Collaborative platforms, when they materialize as physical infrastructure, are places where technological innovations melt together to deliver more value and often lead to development of new technologies. Already this short summary makes it quite apparent that establishing such platform and keeping it running requires substantial investments, and that such infrastructure must continuously attract and train scientific staff with expertise across multiple disciplines.

Collaborative platforms for engineering biology

While my focus in this summary is mainly on physical infrastructure (so the first two bullet points below), more abstract arrangements also further the mission of collaborative platforms. Zooming on engineering biology, those are the platform the paper highlights:

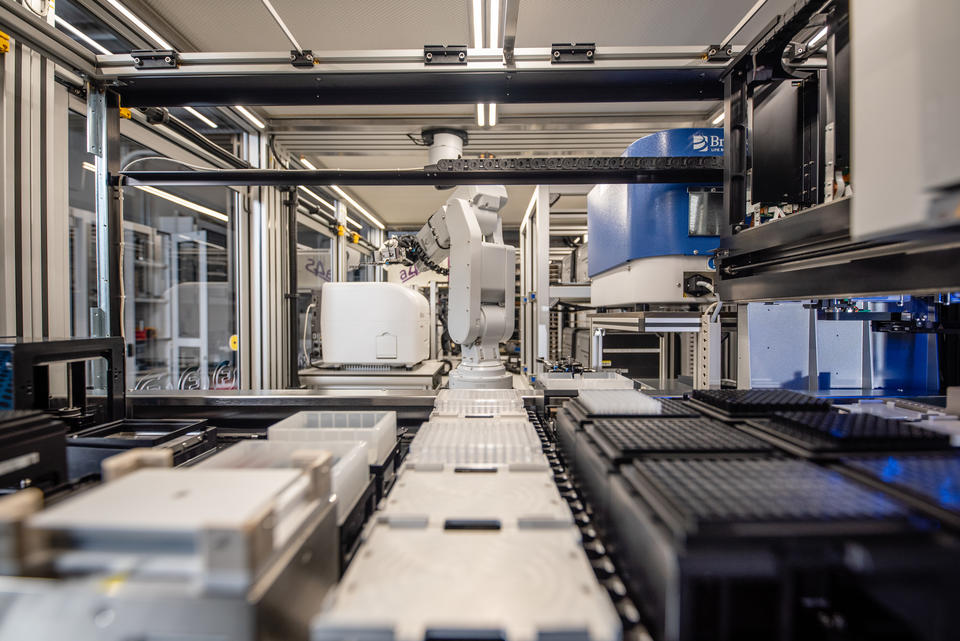

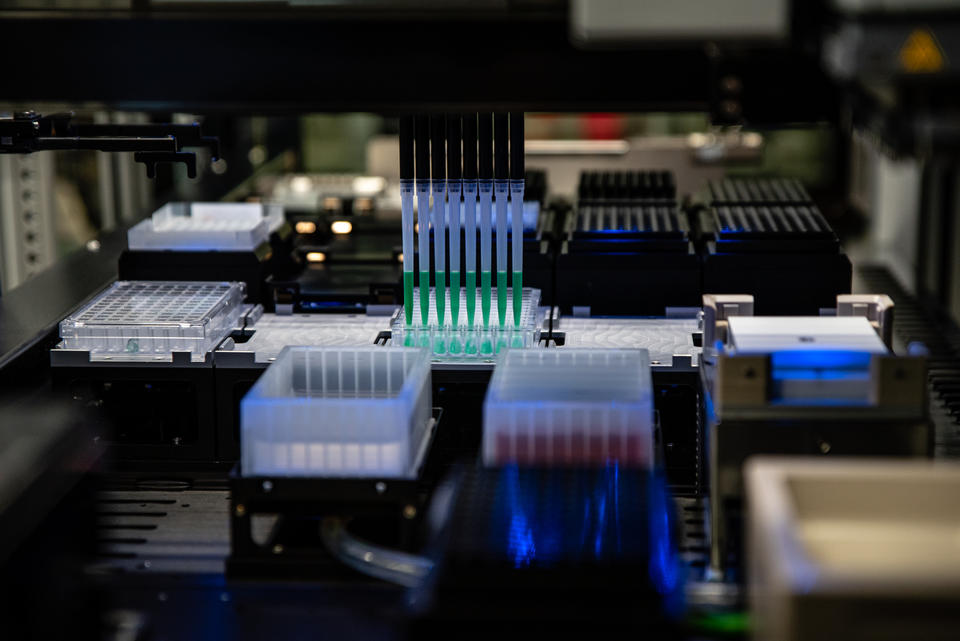

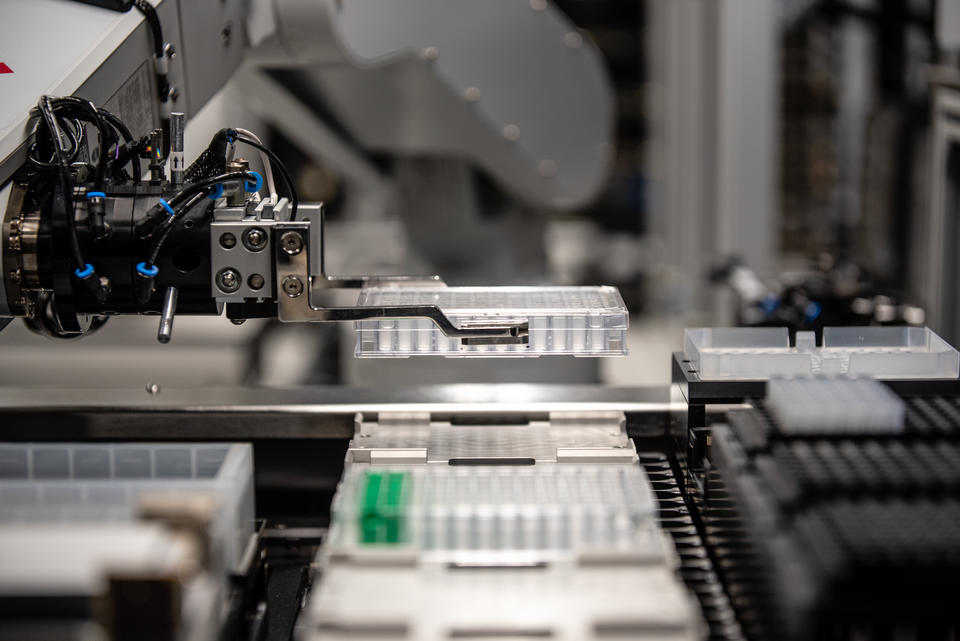

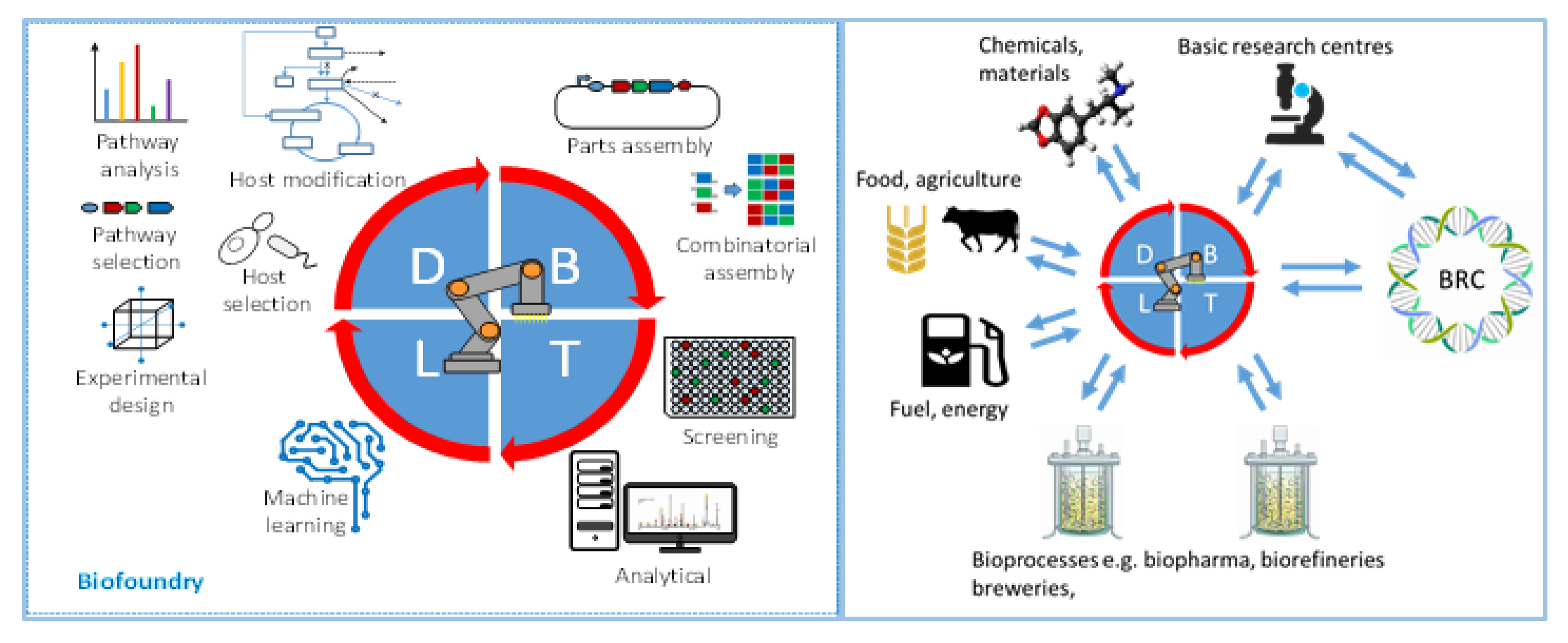

- Biofoundry: highly automated facility implementing Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle

- Biological research center1: a physical repository of molecular biological diversity (basically preserving cells of many organisms together with their annotated genomes)

- Human capital infrastructure: an abstract place where core stakeholders and top researchers in given field interact (in practice this can be independent advisory bodies or boards of research consortia such as EBRC)

- Demonstrator facility: Infrastructure between pilot and full scale production

For now, lets keep the focus on biofoundries. Note that while they are the most often thought of as centralized, it can also be a network of distributed infrastructure units (such as Agile Biofoundry in US).

Policy suggestions for design of collaborative platforms

The meat of the paper is in providing suggestions for policy makers on how to successfully kickstart collaborative platforms. We already know that this is one of the important ways how to incentivize innovation in biological engineering as government involvement in collaborative platforms can incentivize and de-risk private investments in emerging technologies. The overall goal should be to make the platform as accessible as possible across sectors for various actors across sectors as its increased usage will mostly lead to its increased value for existing and new users (so called network effect). Here are the major recommendations from the paper as I identified them, with added accent on biological engineering:

- Design access and IP policies that maximize usage of platform’s resources and interaction among users (e.g. smaller actors pay less)

- Consider education and training as created value

- consider also professional training and collaboration with institutions other than higher ed (such as vocational schools, community colleges, …)

- contribute to undergrad and grad programs by providing platform to develop more tech- and data savvy- biologists

- Offer job security despite project-based funding (long term commitment needed)

- Leverage collaborative platforms as spaces to implement shared mission, potentially across borders (e.g. development of new sustainable materials and food products or biosurveillaince)

- Standards are necessity and should be implemented via industry consensus with sufficient flexibility to allow growth and innovation

- Implement strong data management systems

- Use collaborative platforms as space to engage with broader society (e.g. build a productive two-sided dialogue around GMOs)

- Next to private investments, judge platform performance by other metrics, especially in early stages (patents, job creation, publications, …)

- Life cycle analysis (LCA) of new products to demonstrate their sustainability in robust manner is likely to become more common. Consider adopting it early.

Governance of collaborative platforms

Markets are commonly not entirely in place for emerging technologies and collaborative platforms help to shape them through various modes of governance. Here the most salient points from the report on this topic:

- Emerging technologies are most often governed collaboratively, by governmental and private actors. Development of governance often includes feedback from civil society.

- multiple strategies are often pursued simultaneously

- governance both top-down (e.g. restrictions on access) and bottom-up (standardization and propagation of social roles and values)

- Standards delivery competitive advantage and support network effects2

- create compatibility, facilitate automation

- provide assurance of safety and quality and thus enhance consumer and investor confidence

Approaches to govern intellectual property in collaborative platforms

Collaborative platforms are by their definition places where different actors across academia, industry and public sphere come together, often with the goal to innovate and develop new products or technologies. How such platforms will manage intellectually property (IP) is a critical design decisions that they need to take early on. Here are four possible ways how to do so:

- Platforms own IP

- IP is held and managed by parent research institution

- IP policy depends on platform usage or project type

- Collaboration agreements determine IP rights before the project onset

Currently, the most prevalent mode of IP management at collaborative platforms, and in particular in biofoundries, is number 2 - IP is held by parent research institution. While this has been a common practice in academic settings, it is rarely attractive for private partners, which would usually prefer approaches 3 or 4 that give them more straightforward access to the resulting IP. In option 3 this could be for example by buying IP rights for project’s cost plus some form of ‘success fee’ derived from commercialization success.

Conclusion

Collaborative platforms are important hotbeds of innovation, with marked importance for emerging technologies and markets. They can have wide spread positive impacts ranging from implementing ‘mission-type’ solutions (e.g. as responses to societal and environmental issues that are not currently economically viable and may have to be incentivized), crafting fields’ governance, accelerating technology transfer, and managing open debate with public, among many others. In the field of biological engineering, biofoundries are the most prominent examples of collaborative platforms with physical presence. While many countries have already embraced this paradigm, many more are still considering it or lacking further behind. The recommendations and experiences highlighted in the report, while useful across the board, will be of the most use to policymakers and stakeholders in early stages of platform establishment, who seek to install good practices in this rapidly developing space.

Footnotes

comments powered by Disqus